Analiese Melendez on "Living on Purpose"

A: I'm trying to mess with my audio. If you can hear me, do a reaction, a little Zoom reaction. Okay, can you hear me?

J: Yes, I can now.

A: Can you hear me? Okay, nice.

J: Yeah, yeah.

A: Okay, slay. You're just gonna have some jazzy music in the background.

J: I love that. I love that.

A: Sorry.

J: Well, everyone, in the case that I edit this and upload it to the website as an audio file. My name is Jackson. I'm an editor and partner here at Everything Matters Press and today we'll be talking with Analiese Melendez. Analiese is an old friend who I used to play D&D with. They are also a Tampa / Central Florida-based artist focusing on installation work and sculpture practices. Their work often explores themes of identity, community, and healing, and they work with a lot of mixed media, performance art, and digital media, an ever-expanding array of different stuff. So welcome, Analiese.

A: Thank you so much. I'm really excited to talk with you today!

J: I appreciate it. So what can you tell us about “Living on Purpose?”

A: So a lot. “Living on Purpose” was a piece I created as an homage to all the different versions of myself, growing up as a Floridian, as a woman, as a survivor of suicide attempts. And it really was…a good point for me to celebrate my successes thus far and celebrate my identities thus far. I really think it's important to talk about struggling with mental health and also to talk about pride and where you come from and the point where those two things meet So…Yeah.

J: So what's your artistic philosophy? What is it you're setting out to do with this piece or just in general as an artist?

A: I definitely think…in my body of work, it's important to me to educate and bring awareness to many different topics in ways that are approachable to the public – hence my stylistic choices because I feel like it's difficult to talk about really nuanced topics like suicide and identity and trauma and the things that make people who they are without getting too dark and twisted and stuff. So I really try to approach these topics in a way that make people feel comfortable to talk about them. I find throughout my body of work, I talk about death a lot and I talk about growth and I talk about survival and thriving. And these things are often looked at through a lens of like grim approaches. I do think that because they are so widely experienced, it's important to try to approach these topics in ways that are digestible and make it easier for people who may be more hesitant to talk about it to be able to relate and open up. I've had a handful of times where pieces that I've published have touched the right audience and it's really rewarding to hear from these people that "oh I actually went and got a diagnosis because of your piece. I didn't realize that the way that I was living was neurodivergent or I actually am a survivor of this, this, that, and your piece really resonates with me in the fact that it's important to celebrate how far we've come since then." So yeah, my goal with my work is to just explore how to bring people together in these difficult topics and how to better bring nuanced conversation from people who experience difficult things. As well as another huge part of my body of work and even in this piece is conservation and…once again, education. I was very purposeful in Living On Purpose to bring only Florida native species into the exhibition as a passive education attempt.

J: Noice!

A: So…yeah, I think education and awareness are really the two biggest pillars of my body of work. And this piece is really an homage to all of those things.

J: Gotcha. Accessibility and education. I have this idea that your work is— well you're really into tactile, immersive installations over more traditional mediums.

A: Mm-hmm!

J: What's behind that? Where does that preference come from?

A: I think that comes from my own experiences. I am currently finishing out my Master's in themed experience and a big thing about themed experience is exploring all of the elements of a tactile space and how those things create memory. And so in the art that I create, I find it important to try and explore all avenues of interpretation, whether it be smell or sound or textures. Any of those things are an opportunity to create a memory and to create a connection between the pieces that I'm creating or whatever I'm trying to educate people about in a way that's more meaningful than just a plaque on the wall.

J: It sounds like the music in the background kind of stopped.

A: Okay, sorry. Good.

J: No, go ahead. All good. It was a nice backdrop.

A: Let me see, where should I go next?

J: Well, in that vein, we've been talking about like the haptic, sensorial qualities of your work. Do you have neurodivergent people in mind as your audience when you're creating these installations?

A: Oh, absolutely. Accessibility is an integral part of the pieces that I create. I think that's why I try to explore all avenues of interaction because if somebody is blind, they should be able to feel what I'm creating. And if somebody is deaf, they should be able to see what it is and smell what it is. I think accessibility for neurodivergence and differently-abled people is extremely important in the work that I do because you can never pay attention to the people in your community enough. I think it's often overlooked by designers and artists who are trying to maybe serve one or two different kinds of people that like, okay, maybe my cousin can't walk, so I'm going to make this designed in a way that my cousin can experience it. But I want to try and make it so that everybody can experience the things that I create, including that cousin and everyone else I may not know yet.

J: So in this installation are the people coming to see them allowed to touch most of the-

A: Oh, yeah. Most of the installation.

J: Okay!

A: Yeah, I really like using textures and fluorescent colors and strange audio. I want people to be able to interact with the things that I make as much as possible and it's often encouraged. Another piece that I created was a puzzle. It was a six foot by six-foot puzzle. It featured different versions of me that I had at the time believed were the “ideal versions of myself” and I used it as a representation of the fact that your community really builds you up. And so I had my peers put the puzzle together and they stepped on it and they picked it up and they threw some pieces away and that's exactly how I expect people to interact with my work, it is as tactile as possible.

J: So could you tell me all the different mediums you used in this project in Living on Purpose? In the process of making this piece did you learn any new ones?

A: I don't know I can list them all, it was a lot definitely. I wasn't as experienced with murals before this project as I am now because this was I think over 100 feet of material by eight feet tall that I was painting on. So that was a new one for me. And so I had used house paint because I really like using latex house paint for my pieces because a lot of the stuff that I paint on is pretty flexible and that allows the give in that paint to be able to hold up to it. I did use 500 pounds of sand so that when guests walked into the installation, they felt like they were walking on the beach. And that followed up onto the mural where applicable so they could touch the mural and feel that graininess. I also incorporated elements of sound. I had tried to emulate the feeling of being underwater and just like sitting there kind of cross-legged under the ocean, hearing what you can hear around you. As well as light, I had used some children's nightlights that rotate to make it a more modular space.

J: What else did you do?

A: I did learn a lot about using the CNC routers to be able to carve out full-scale fish species. Like the grouper I had. It's a full-scale six-foot grouper, a Goliath Grouper named Bertram. And that one I did not encourage people to touch as much, but I had a lot of hidden elements in the sand and I had the smells of the beach and sunscreen and such…Yeah, I don't remember what the question was. Haha sorry.

J: No, no, that’s perfect… And then there's also a bit of digital animation with the-

A: Yes!

J: -the sun, right?

A: Yes, I do actually come from an animation background. When I first went into undergrad, I had thought that animation was my goal in life and I quickly found out that I loved the product of animation but I wasn't absolutely in love with the process as much as my peers were. And so I fortunately, through the University of South Florida arts programs, were able to work with Irineo Cabreros Jr, my mentor and one of my most valued friends, to learn that physical media is really what spoke to me and getting my hands into these materials is what resonated with the messages I was trying to put out. So I did have the animation elements, and I do continue to this day in my portfolio and in the work that I do, incorporate those elements. Kind of going back to what you were talking about with the multifaceted multimedia approach.

J: So you brought up the materials. I know you’ve spoken about how having grown up in poverty here in Florida affects your decisions with regard to materials. Could you tell us more about that?

A: So I am a Florida native. And the first place that I lived in was actually one of those tool sheds that you can buy at Lowe's. It was in the back of my 17-year-old dad's backyard — his parents' backyard. And we had just whatever I could scrounge together from around the neighborhood any pallets, any cardboard off the side of the street any random stuff that I could come up with to start working with. And I feel like even though now in a much more fortunate position, I've worked really hard to get to a better place physically and mentally, I still have such an appreciation for scrounging things together and finding the value in reusable materials. Kind of as an homage to my younger self and to others who may be experiencing similar situations, but also as a point of recyclability and using what you already have. I think it's important to find purpose in limited-use items. So most of the materials I used in this project were reused, repurposed, or bastardized in some way. I tried my best to make it memorable to the original objects. For example, some of the corals, many of the corals and sponges that I had featured were dead creatures, because you know sponges and corals are creatures, had washed up from a previous hurricane and all of them had been drying out in the sun. And so I kind of brought life back to them to honor what they originally were.

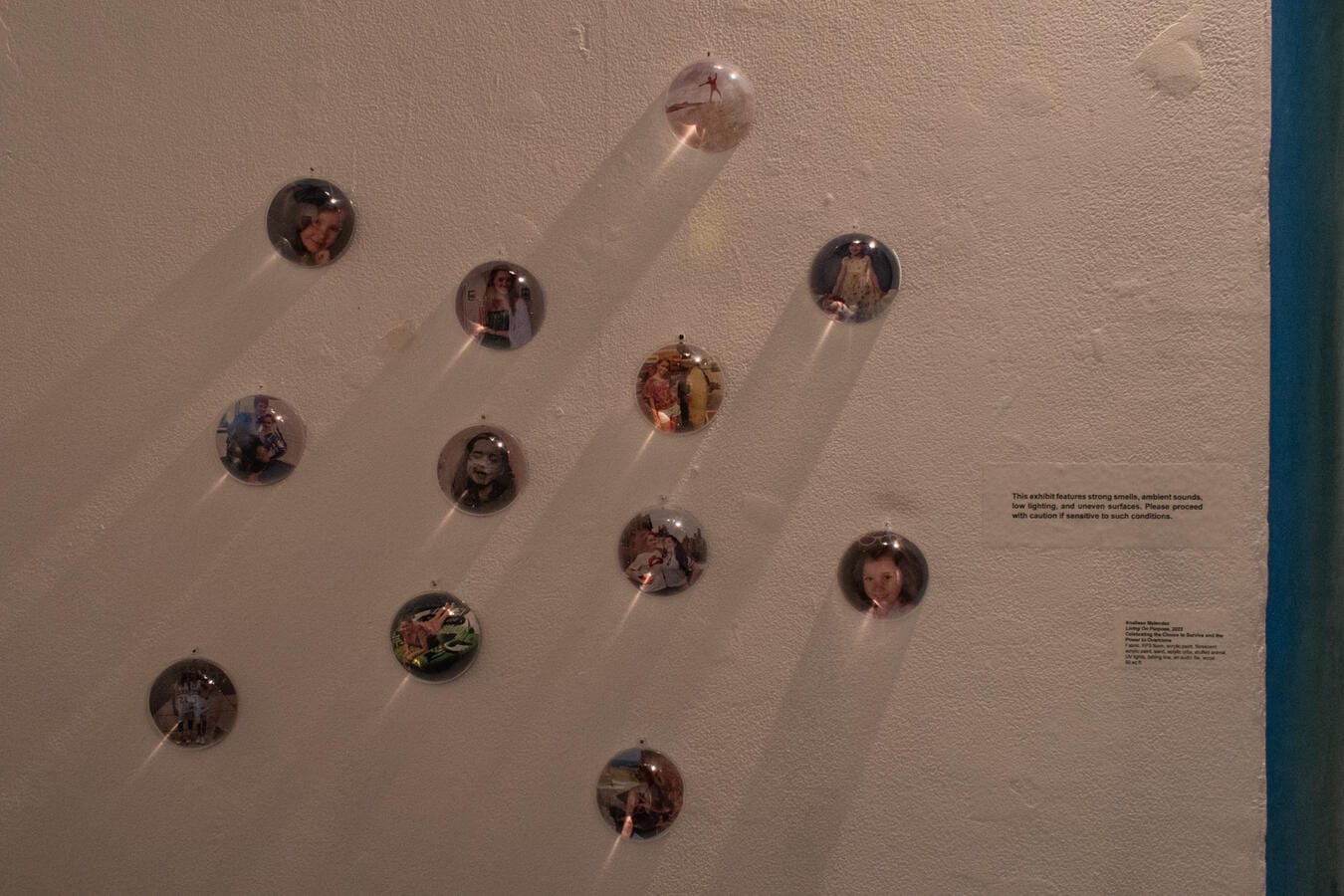

J: Cool. I love that. So, I'm looking at the little girl in the sailboat with what appears to be a stuffed animal elephant. Could you tell me about the story and process behind this part?

A: Yes, yes. So that elephant is named Ellie that is my oldest friend. I've had Ellie since the very second I exited the womb. And now 23 years later, I still sleep with her. So that little baby is a picture of me and all of the people included in that mural are representations of me growing up that I found through different photo albums. And so that little baby Ana was like the first time I had doubts about my worth at that little tiny age because I had lived in an abusive household. My mom, both my mom and dad were like 17, I think, when they had me and now at 23, I can't even imagine what it would have been like for them. But I know that it fostered a lot of animosity, maybe unintentionally from them to me. But that little small child already was having thoughts of maybe I don't deserve to be here and I shouldn't be around and I'm just like wasting my parents time and space. But things like art and nature and my little elephant kind of helped me keep grounded even at such a young age. So the featuring of that was really just paying respect to that smallest version of me with those first doubts.

J: What does it mean then to put that little girl, your younger self into this boat adrift with Ellie?

A: She was there for the celebration. Every version of myself in that mural got to be together for that moment to celebrate, wow, we made it to college. We lived long enough to make it to college, 20-something years old and finish it! That to me was me talking to her, talking to the teenage version of myself that I painted, talking to the middle school version of myself that I painted, and getting to all be in the same space at the same time and going, wow, look what we've gotten to do, guys, because we didn’t decide to end it or run away.

J: Yeah. That's really something. I'm tearing up a little bit. I also wanted to ask, you cite artists like Lucy Sparrow, like Hope Ginsburg as some of your influences. What is it about their work that resonates with you?

A: Oh, so Lucy Sparrow is this really cool artist who I find her work to be interesting because it's very cute and kitschy and oftentimes in the art world, especially like the most prestigious parts of the art world, cute and kitschy is frowned upon. And even in my experience at this entry part of the art world, cute and kitschy is not profitable and it's not identifiable for part of the population and so it's discouraged - there's a lot of sexism tied to it. So it's really interesting to me to see a successful female artist making cute work that is intercontinental and getting to visit her exhibitions and bringing that cute, kitschy aesthetic into my work, which has always inspired me. Being a Floridian, kitsch is like what I brought up on. So it's really important to me to see female voices empowered like that and that, okay, because I make cute stuff doesn't mean that I'm not going to be successful. And then as far as Hope Ginsburg, she’s a person who blends the hard sciences and art. And I think that that's extremely important. Many times in history people have paid attention more to discoveries in science and possibilities in science because artists worked with them or they delved into the arts to be able to find an avenue to broaden their message and Hope Ginsburg did this really interesting piece about sponges. I was introduced to it with the Sponge Exchange where she worked with USF students. Previously she had worked with other scientists to blend living sponges, which they continue to live as you blend them, and sculpting a garden with these sponges in the ocean to regrow an entire ecosystem. I think it's really inspiring to talk about the intersection between scientific accuracy, discovery, and appreciation, and also artistic ambition. I think people want to listen more to educational things when it's fun, when it's interesting, and I want to be able to make that bridge between those two things.

J: I think I'm right there with you on both accounts. Why do you think kitsch and cuteness are such good vehicles for exploring trauma?

A: I think it makes it more approachable. Sometimes you'll see stuffed animals of Chlamydia, like different diseases as little stuffed animals, and people buy them and they go, “Okay, I can talk about this because it's this cute, funny little thing and like haha,” but it's a serious subject. I have this fun thing, this outlet to be able to discuss it through. Kitsch is something that I've been completely surrounded by as a native Floridian in Weeki Wachee, Gatorland, and in Disney World, I suppose. And any of the cute like citrus citrus stops along the highways.

J: Oh, I love those.

A: They're so much fun! I love them. And to be able to use those avenues are an "easy in" with the public. It's bright. It's flashy. It's attractive. And then now that they're already there, let's talk about serious stuff in a way that is not so intimidating. Kitsch and cuteness allow people to open up more when I talk about PTSD, autism, ADHD, and when I talk about suicidal thoughts — it often becomes this really heavy, heavy, heavy conversation. Or if you're working with people who are also survivors or like-minded in these ways, often they can come to talk about those things from a point of humor. Obviously, there are some conversations that are more serious and intense when people are struggling, but when you're talking about surviving and you're talking about getting through things often the reality is you have to use humor and cuteness, kitschiness and jokes to work through them and celebrate that you've gotten so far as you have. I would say approachability and celebration are important with kitsch and cuteness towards heavy topics.

J: And is that kind of harder to do given Florida's current political climate being really antagonistic for marginalized communities?

A: Absolutely.

J: Would you say the past couple of years of DeSantis, or this crap in general, has changed the direction of your art?

A: I think it's fueled it. It's always been important, but gosh, it's so important to everyone to be in an open dialogue about trauma and change right now— especially for people who maybe don’t want to talk about these things and even for those who haven't experienced these things. We need empathy to be able to approach and have interest in these topics. I talk a lot about queer identity as well, which in this topic is also a sticky situation. And I have spoken to viewers of my work who find comfort in the fact that I am so boldly approaching these topics, but in a way that they could show it to their bigoted uncle and be like, hey, look at this thing. Maybe let's talk about it. That sounds good.

J: How does queerness kind of show up in “Living on Purpose?” If it does at all.

A: I do think it shows up more in my other pieces. I think…not every piece that a queer person creates has to touch on their queerness because, in 2024, it's something, I hope at least, is more of a normalized situation. When guests experience Living On Purpose, I don't think that queerness is at the forefront of their thoughts, but as the artist, I definitely look back on it and I know that some of the reasons that I was thinking about ending it in some of those stages of my life is because I was queer and either didn't realize that's what it was or I was told by — not my family because my family is very supportive — but by others that it wasn't okay, especially in Florida. And that I made people uncomfortable and that this middle schooler was a horrible person because she was in love with her classmate. But I don't think that queerness shows up as objectively in Living On Purpose as it does in some of my other pieces.

J: Fair. And, I appreciate you sharing that with me.

A: Of course.

J: I wanted to ask, I absolutely love this one scene of like a very beachy bench with some snacks next to it with, I don't know what type of plant this is, but I'm looking at this and it looks so like…

A: Yes. Yes.

J:...like Florida Boardwalk-y, could you tell me about this? What's going on here?

A: That is exactly what I was going for: Florida Boardwalk-y. I was trying to make a transition in the gallery between everybody else's pieces and my own because I know that Living On Purpose, the main aspects of it are very immersive and immersive and odd. They're very bright, the color choices that I had gone with. By doing this boardwalk section with the community board and the photo op area and I had left a working camera with film in it for guests to be able to utilize and put onto the community board, that created a midway point between the rest of the gallery and the fully immersive section of “Living on Purpose” and also continued to celebrate like things that I grew up with. I learned about so many different people and organizations through these community boards at different beaches and trails throughout Florida, I wanted to allow other people in the gallery and in my cohort to be able to put their information up there as well as those Polaroids that I had provided the film and camera for. And now I still have all of those things displayed with Bertram in my office.

J: Gotcha.

A: So yeah, it was a good midway point.

J: But what did you do with the 500 pounds of sand is my question.

A: So some, I'd say about 100 pounds of the sand is part of the murals. I kept the pieces that I resonated the most with of those murals, I cut them out. It was painful to cut all of it, but I did it and I kept the pieces that I liked the most. And the rest of the sand I actually donated to the University of South Florida art department because they have a section of their department where people do bronze casting and metalworking. And so for safety, a large portion of that is covered in sand for fire prevention and it was fortuitous in that situation to be able to help them bring sand back into that area.

J: That's awesome. Recycling queen. What does five — at the risk of sidetracking the interview now— what does 500 pounds of sand even look like?

A: Dude, oh my God.

J: Like in like a physical space when you've bought it?

A: The people at Lowe's, they're very familiar with me. 500 pounds of sand looks like enough for you to be able to sit in it and put your hands through it and not exactly touch the floor, unless you dig a little bit deeper. It was just enough sand so that people really felt like they were walking into the beach and I had so many people who experienced that piece tell me how much the sand element helped with the immersion and made them feel like they wanted to sit there for hours. Yeah, that's what 500 pounds of sand looks like.

J: That's awesome.

J: Well, I guess that leads us to our last question. What is it you hope people take away from “Living on Purpose?” Besides sand in their shoes.

A: Let me think about that... I think people should take away it's important to celebrate your successes and how far you've come from wherever you came from because most people come from something of difficulty. It’s important to celebrate yourself here and again so that you don't spend your whole life just surviving and surviving and surviving and then you die. I think it's important to take away from Living On Purpose the value of talking about things that you go through. That comes up again and again in my body of work that talking about these difficult conversations leads to people uncovering things that they may not have wanted to talk about before or they weren't encouraged to talk about before or they didn't even know to talk about, pursuing avenues of help or growth. I hope people take away from Living On Purpose that where you come from is important and it can be beautiful — and to think about what you can do to help your community and talk about the things that you've been through, what contributions you could possibly pursue to bettering those around you. I want to make people aware of these things so that they can get talking and maybe save a couple lives in the process.

J: I appreciate that. That's really thoughtful, dude. That's all I got. Thanks again for sharing with us. I loved looking at your work on Instagram when it first came out. And it was awesome to hear more about it and your process.

A: Thank you so much. I really appreciate you talking to me about it today!

J: Sorry, the audio cut out.

A: It's okay.

J: But alright.

A: Alright.

J: Insert outro if I was a podcaster this is where the outro would be.

A: So true.

J: We're also limited by the fact that I only have the 40-minute free trial of Zoom.

A: That's fair.

J: But you take care. You take care. And we'll be in touch.

A: Thank you. I really appreciate you talking to me about this. I was so excited to discuss this with you. I've been bragging about it all week.

J:My pleasure. My pleasure. Let's goooo.

A: I've been telling people about your website. I'm like, guys, look at these people want to interview me. Look at their website. You should write it down. They're so cool.

J: The other two partner/editors [Yo and Will] are way cooler than me. But…

A: No, I think you're cool! Shut up!

J: I appreciate it. Make sure you also plug the Florida Manifesto. We got to sell, sell, sell, you know.

A: Yes, of course. Also, I gotta plug Zoo Tampa. I gotta plug the Florida Aquarium. I gotta plug the University of South Florida. I gotta plug the University of Central Florida. I gotta plug the Thirsty Topher in Orlando and I gotta plug my instagram @ana_mations!

J: Yeah. Shout out Florida Citrus Center. Rest in peace Wannado-

A: Wannado City! Rest in peace, Wanado City! You know what's so funny? When I was growing up I went to something like Wannado City, but it wasn't called Wannado City. I worked in the Busch Gardens section there, making little animal masks for people. Little did I know like a decade later, I would still be working with animals and I'm trying to do that for the rest of my life.

J: I always really liked the mining gems little activity and the firefighting. Yeah. And so naturally I synthesized those two traditions and became an English as a second language teacher so there you go. Yeah.

A: Wait. Now, okay, I'm pretty sure Wanado City and JA BizTown are the same thing, but have you heard about JA Biztown?

J: No, as long as I knew it, it was Wannado City. But we're talking about the one in Cypress Mall now?

A: No, actually. I didn't do Wannado city. I thought for a long time those things were the same thing, just different names. I did JA BizTown.

J: There's like a chain of them. I think one of them is like, or not a chain but like —you know?

A: I'm going to Google it. I'm Googling it right now…It was, while both JA BizTown and Wannado City are both educational experiences where children role-play different careers in a mature city setting, the key difference is JA BizTown is primarily a school-based program focused on financial literacy through curriculum integration. Wannado City was a standalone for-profit entertainment center where kids could simply play different roles in a metro-city environment.

J: Okay. I have no idea what that means, but I think our Zoom meeting is about to end.

[Zoom meeting ended]